After Dobby died in 2018, everyone asked why I didn’t get another capybara. I was 67 at the time and Dobby had lived 9-1/2 years. I know what it’s like to wrestle a full grown capybara into a car, and I did not want to do that at 75 years old.

As it turned out, city ordinances changed and I would now have to convince the city council that capybaras are cute, benign animals. My fate could be determined by one cranky councillor angry at a neighbor with an obnoxious barking dog. By far, my biggest obstacle was finding a new veterinarian. Dobby’s veterinarian had moved to a clinic an hour north of here that only accepts dogs and cats as clients. Dr. Vincenzi and I cried together when he euthanized poor old Dobby, but his new clinic simply did not treat exotics. That, to me, was the biggest obstacle to getting another capybara.

When I first started looking for a capybara, I asked my veterinarian if he would treat my pet. Dr. Vincenzi was enthusiastic. (Much later I learned that his father had been a veterinarian and director at Seattle’s own Woodland Park Zoo, providing service there for over forty years.) When I told him (six months later) I was ready to retrieve my pet capybara he was stunned, perhaps a bit less enthusiastic, but still amenable. He had never treated a capybara.

Dobby and I flew home from Texas and arrived in freezing weather. His carrier sat on frozen tarmac for half an hour as I paced in baggage claim. Ten days later I observed my silent, docile capybara and wondered whether he was thriving. He slept a lot, wandered the house silently, ate once in a while. I have enough experience to know that baby animals bounce between manic zoomie sessions between naps. They are frisky and vocal and ravenous. His nose was a bit crusty. Dr. Vincenzi listened to his chest and suddenly we were treating little Dobby for pneumonia. Dobby lost a month’s worth of growth but he grew strong and healthy and he eventually attained a normal weight for his age.

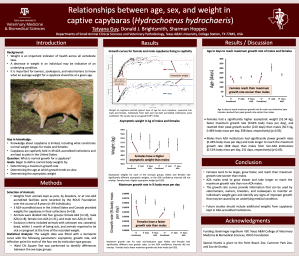

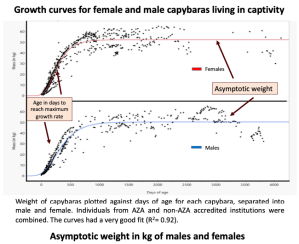

- ROUS Foundation funded study

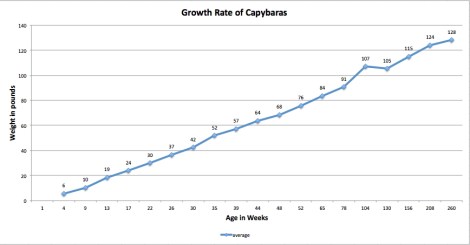

- The weight chart graphic

The only reason we know that is because of the Why Weight? study done by the ROUS Foundation. The lack of information regarding capybara veterinary care prompted Melanie Typaldos to found the ROUS Foundation.

You can read about the Why Weight? study at our website, and both Melanie and I have written about it extensively.

Weigh your capybara!

Small capybaras are so cute that even a capybara near death from starvation will look healthy to a veterinarian not familiar with the species. We see it over and over and the necropsies prove the point.

- Gari gets his teeth trimmed

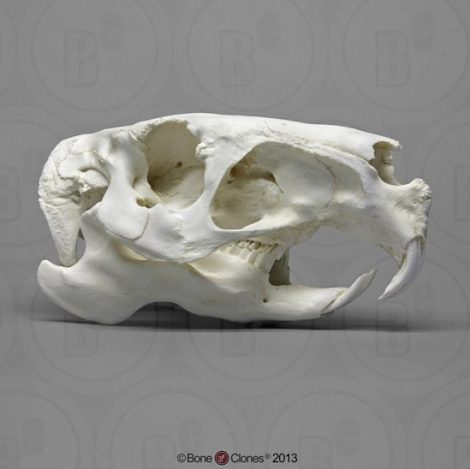

- Gari’s teeth and skull

Today, though, I want to emphasize the importance of having a well-informed exotic animal veterinarian. Dobby would never have made it to his second month without Dr. Vincenzi. Melanie’s capybara Garibaldi, a rescue who had never been outdoors, developed dental issues due to early poor nutrition. His bones didn’t develop enough density to support his teeth properly. He needed frequent tooth trimming and eventually needed extensive dental care . We drove over two hours to Texas A&M for dental surgery, where one incisor was removed and he was treated for an infection in his jaw.

- The veterinary dentist takes a look

- The dentist removes a loose incisor

- The incisor nearly fell out of his mouth

- The dentist completes the exam

- I count ten observers, do you?

- The veterinarian takes over for the cleanup

- The veterinarian finishes up

- The anesthesia is reversed

Just last week we heard of a young capybara in the ICU who had been treated with penicillin, a drug notoriously toxic to guinea pigs. We’re still waiting to hear if that one survived. We’ve heard of capybaras treated for malnutrition and scurvy, we’ve seen broken legs, frostbite, toxicity from poisonous plants, and more. All easily treatable for dogs and cats, but good luck bringing a 135 pound capybara to your local emergency care clinic. They won’t let you in the door.

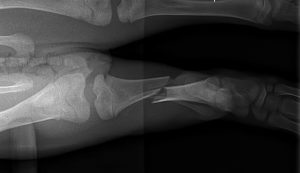

- Broken leg

- Close-up of break

- Frostbite on all fours

Once when Dr. Vincenzi wasn’t available, I took Dobby to a new nearby exotic animal clinic. Dr. X had treated a bobcat the day before, explaining Dobby’s extreme reticence to entering the exam room. He was there for a simple blood draw, something I had watched Dr. Vincenzi do several times. Dr. X needed to sedate him for the procedure and I agreed, though I was not allowed to watch. Two hours later, a tech brought him out and explained that somehow during the exam and blood draw his two upper incisors had fractured. Dobby was still so sedated he could barely walk to the car.

- Teeth broke off at gumline

- I found the teeth out in the garden

His teeth broke off two days later and I hand fed him for weeks after while they grew back out. He now walked painfully, with a permanent limp. My guess is that as Dr. X sedated him, Dobby passed through the usual “excitement” stage of sedation unsecured. He thrashed and fell off the table, breaking his teeth. Or maybe the sedation went sideways and they had to intubate him, which can break incisors in smaller rodents. At some point, they must have tried to yank him back onto the exam table by his right rear leg. (His subsequent necropsy indicated he’d had an injury to that leg.) He gradually lost weight and I treated him for pain during the following two years until his death at 9-1/2 years. By that time, Dr. Vincenzi was again treating exotics, which was fortunate, because I would not have trusted Dr. X to euthanize him.

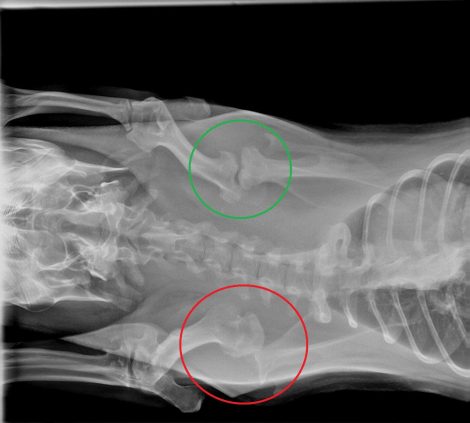

The incisors are large and require dense bone to hold them in place. They grow continually from a tooth bud way back in the skull- follow the curve of the tooth to get the idea.

I will say this once more: find your vet before you find your capybara. The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) estimates that only 3-5% of practices in the US specialize in exotic animals. That means 95-97% treat dogs and cats only. “Exotic” can mean anything from birds and reptiles to rabbits and guinea pigs, but it usually excludes poultry and livestock. It never means capybaras. If you are lucky enough to find an exotic pet specialist who is willing to risk it all and take on a zoo animal, it’s a good day to buy a lottery ticket.

Capybaras in the wild graze 24 hours a day. Your pet needs continual access to fresh vegetables and fruits.

I’m deadly serious when I say to find your veterinarian first, before you bring home your pet capybara. Where do you start? Ask your current veterinarian for suggestions. Don’t even think about zoo veterinarians. That’s a full-time job and they aren’t going to have time to treat your pet’s emergency, even if the zoo was willing to allow your capybara access to their facility. They may be able to recommend someone but I wouldn’t wait until you have an emergency to ask around. Urban areas are more likely to have exotic vets but driving your capybara into downtown for an exam or emergency is challenging. (Remember- 135 pounds of stubborn animal with razor-sharp teeth) Rural or farming areas are more likely to have veterinarians who treat horses, sheep, goats, and other grazing animals. They are an option to explore for treating your graminivore. They will often make house calls, which is a plus. Find one who knows what a capybara is and go from there.

The dire situation we hear about the most is the kindly veterinarian who agrees to treat your pet and quickly discovers they are out of their depth. That’s how we hear about critically underweight capybaras who are being treated with penicillin. In an emergency, find a veterinarian who has guinea pig experience. Almost everything we know about capybaras we learned from guinea pigs, from diet and digestive tract to blood values. Many diseases present similarly across species, but the Vitamin C requirement is unique among humans, a few primates, and some rodents, notably guinea pigs and capybaras. A young capybara should receive 500mg daily, and adult 1000mg, a pregnant or lactating female 1500mg. They won’t eat enough unless you do. Read these two studies.

If you are reading this as you frantically search for a capybara veterinarian, there are still a couple things you can do. Take in the weight information above. It will help your new, confused veterinarian to determine how much your capybara should weigh. Don’t accept the “he’s just a small one” verdict. Small ones almost always have scurvy. Do your homework and scour the Guinea Lynx website for information about what meds are safe. Finally, you can call us (ROUS Foundation) to ask for advice. We aren’t veterinarians, but we can help with questions about nutrition and suggest minor first aid remedies. Most likely, though, we will listen to your story for a couple minutes and then recommend that you call a veterinarian.

~~~~~~~~~~

This post was brought to you by Stacy’s Funny Farm, a non-profit pet sanctuary. We hope you will be inspired to make a donation. We especially appreciate monthly giving- the PayPal portal offers that option. If you want to help but are short on cash, head over to Dobby’s YouTube channel. We’re monetized and those ads pay out nicely, so please watch, share, and subscribe.

Stacy’s Funny Farm is a §501(c)(3) non-profit organization.