Capybaras for Home and Garden – Part One

While I was on the breeder’s waiting list for a capybara, I read everything I could get my hands on about capybaras. There was a zoo husbandry survey and Capyboppy and not much else. The husbandry survey drily listed square footage of pens, flooring (invariably concrete), fencing, and assorted food items provided by the zoos participating in the survey. Unfortunately, because zoo animals don’t interact with humans in quite the same way as pets do, zoo information is not very useful for adapting a residence for capybara use. Since then, precious few books about capybaras have been published. In fact, I Can Explain Everything: Confessions of a Pet Capybara, which was written by a pet capybara named Dobby in 2017, is kind of the lone ranger.

Back in 2009, Capyboppy, a children’s book chronicling a pet capybara half a century ago, proved to be more enlightening than the zoo survey. It is a story about a capybara living in a home environment. Capyboppy adjusts well to living in the house as a youthful pet, and has a very nice yard with a swimming pool and lots of grass. As he grows larger, more stubborn, and destructive, they start to pen him in the garage at night. This works for a while, until they can no longer handle him, and he is eventually shipped off to the local zoo. This kind of poor planning is what I hoped to avoid. These days, you are unlikely to find a zoo that will take a former pet of any kind, and re-homing a poorly adjusted wild animal is not easy. Capyboppy caused me to consider that bringing home a capybara and making incremental adjustments to my home might not result in a habitat suitable for a possibly unruly and even aggressive pet.

Moving to country acreage was not an option for me, so I had to consider my current residential neighborhood in my plans. I needed to assume that my capybara might turn out to be an aggressive specimen, and that I might need to devote a major part of my yard to a secure pen for him. Finally, I needed to accommodate for his care if I was not available, out of town, or ill. It wouldn’t work for me to allow a curious full-grown capybara free range of my home if I wanted to leave for a weekend, or even go out in the evening. Trying to explain indoor capybara potty maintenance to a new pet-sitter from a hospital bed could be difficult, as well, and you just never know when that might happen. I had to consider every scenario possible, and anticipate the consequences of turning over capybara care to a “stranger” even for a day.

The pet capybara owners we are in contact with have every kind of housing setup you can imagine. Some people do give their capybaras free range of their home, but these are primarily owners who never leave their pets unattended. The ones we know of also provide continual access to outdoors, which means doors left ajar and muddy paws on the kitchen counter. We don’t know of anyone who has successfully kept an indoor-only capybara. In the wild they spend all day and night grazing on grass and water plants. Unless you live outdoors, it isn’t going to work. Some people, and most of the breeders we know, keep their capybaras outdoors, in a goat-like pen with a barn. Because they need constant access to water and grazing (or hay), an outdoor habitat is most practical for people who live in a mild climate. My capybara, Dobby, was primarily outdoors, though he had daytime access to an indestructible corner of my kitchen. Like a zoo animal, he was securely penned at night, outdoors, with a heated sleeping area. When temperatures dipped below freezing, he was allowed to sleep in the kitchen, though he still preferred his own cozy outdoor bed.

Enough about Dobby. Let’s consider some of the aspects of providing a habitat for your capybara. Remember that these are wild animals, and docile as they are, they can react unpredictably to noises, smells, other pets, and they can become extremely territorial. They are a tropical animal and their native habitat is more Equatorial than Florida. They are not found where freezing weather occurs. They are also not found more than a mile from water. Capybaras are semi-aquatic, and by that we don’t mean they swim sometimes. In the wild they spend a LOT of time in the water, for food, protection, and breeding. They come to land to graze and browse on foliage.

To provide a suitable habitat, then, you must provide security, warmth, swimming water, and grazing. A heated condo with a jacuzzi and a bale of hay is not suitable, and yet, we have had several capybara owners insist that they can keep an indoor capy. They have all failed. Keeping a capy indoors even for two weeks during a long hard freeze is a miserable, grubby, and nerve wracking way to ensure against frostbite, but your capy will take revenge. Think of it as Capybara Cabin Fever. By all means provide a cozy shelter for your capybara, but understand that your outdoor habitat is what makes capybara care possible.

Capybaras need to graze. I can’t say that enough. In the wild, they spend most of their waking hours grazing. Think of them as a tropical deer, or an outsized rabbit. Grass is their primary food. They eat water plants while swimming, and they also browse on shrubbery. The list of wild plants they eat is usually limited to about six plant species. Even so, the greenery they eat supplies them with plentiful Vitamin C which is critical to capybaras. Like humans and guinea pigs, capybaras need supplemental Vitamin C. Lack of Vitamin C can result in scurvy. In capybaras, it often results in malformed bones, and can even cause death.

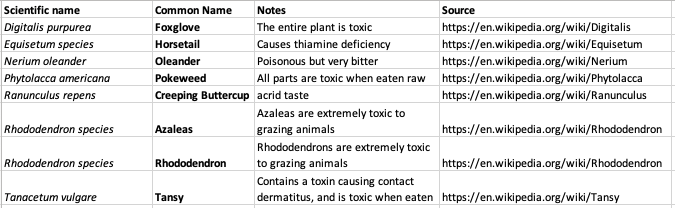

Capybaras, especially babies, don’t seem to understand about our toxic plants, and several pets have died eating poisonous plants (azalea, pokeweed). Those are just the ones we heard about. Check your garden and proposed pasture area for toxic plants. Fence your pasture area so that you can check for encroaching native plants that might be toxic. Local garden clubs and equestrian groups may be a good place to start researching toxic plants found in your area. Your state will have an online list of known toxic plants. I will provide a basic list below for you to start with, but I can guarantee that unless our climates are identical, your list will be different from mine.

Please feel free to comment on the list of toxic plants. We are still learning.

~~~~~~~~~~

Capybaras for Home and Garden is an in-progress capybara owner’s manual brought to you by the ROUS Foundation. Melanie Typaldos and I will post sections as they happen, in no particular order. Eventually, they will become a book, but for now, we welcome requests for information. Online information is hit-and-miss, so our challenge is to compile all these bits into one coherent volume. We don’t claim to know everything, but we hope you won’t repeat our mistakes!